Table of Contents

Abstract

Overview

Suite

Authentication Header

Encapsulating Security Payloads

Security Associations and Parameters

Internet Key Exchange

Operation Modes

Tunnel

Transport

Conclusion

References

Abstract

This document will describe the capabilities and mechanics of Internet Protocol Security as outlined by the Internet Engineering Task Force. Thorough explanations will be given for the purpose and capabilities of the two main protocols, Authentication Header and Encapsulating Security Payloads, as well as both operation modes, Tunnel and Transport. Use cases and example configurations will also be provided.

Overview

IP Security (IPSec) is a suite of flexible and extensible protocols and standards designed by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) to provide built-in security to IP network traffic [1]. It was originally designed and implemented for IPv6 but was later backported and made fully-compatible with IPv4. It’s goal is to provide inherent security to IP, providing security and authentication to all IP traffic at the IP level in the network stack. IPSec is common in environments where remote hosts need secure authenticated access to another network, such as businesses and universities. IPSec provides provisions to ensure data integrity, authentication, replay avoidance, and confidentiality for all IP traffic. It is highly configurable, and allows a wide range of options and modes.

Suite

The IPSec suite is composed of two main protocols, Authentication Header (AH) and Encapsulating Security Payloads (ESP) and several supporting protocols. AH provides nearly full packet authentication and integrity checks with low computational cost. ESP provides encryption and/ or authentication through a flexible and extensible set of algorithms. Security Associations (SA) and Security Parameters (SP) provide the details needed to establish and maintain connections between IPSec endpoints. The Internet Key Exchange (IKE) protocol provides a framework with which to securely communicate the information needed to create SAs and SPs.

Authentication Headers

This protocol provides the mechanisms for verifying packet data integrity and the source address. Verification is provided by the hashing algorithms supported by AH, such as SHA1 and MD5. Supposing both clients have a non-standard hashing algorithm, IPSec allows them to use that in place of the required standards. AH does not provide any form of encryption to any part of the packet, meaning that the full contents can be sniffed and revealed by third parties.

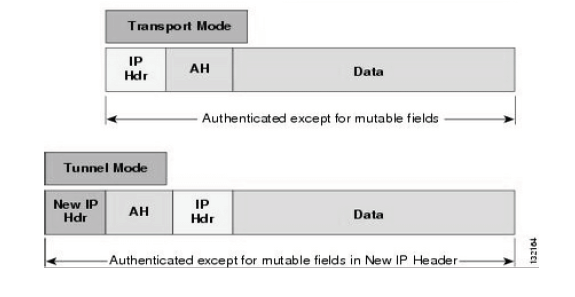

Figure 01: IPSec AH IPv4 Header Format [2]

AH authenticates the entire inner packet payload, as well as all fields of the header that don’t change during the course of routing to its destination, such as time-to-live and next-hop. However, it does verify source address and port, unfortunately making it incompatible with Network Address Translation (NAT) [3]. Routers use NAT to share their IP address with the clients that are connected to them. This reduces the number of IPv4 addresses required to support the growing number of internet connected devices and provides security to the clients. Without port forwarding on the router, the clients services, such as network file shares and web servers, are inaccessible from the outside the Local Area Network (LAN).

Additionally, AH can provide replay attack protection by verifying the sequence number on the packet. However this isn't required and it must be stated in the client's Security Association that the sequence number must be checked. Encryption and confidentiality usually seem like the standard for security, but depending on the application and environment, authentication may be enough. It is also less computationally intensive, which makes it better suited for embedded or extremely high network utilization environments [4]. Also, since the authentication data is kept in it’s own partition of the packet, systems that cannot or choose not to support IPSec can still receive and route AH packets since it doesn’t interfere with or change the original packet’s contents. NAT incompatibility can be solved through NAT Traversal techniques. Many routers provide the following specific IPSec Passthrough instructions which allow IPSec to pass through NAT [7].

Protocol or Port Purpose

--------------- ----------------

UDP, Port 500 Internet Key Exchange

IP Protocol 50 Encapsulating Security Payloads

IP Protocol 51 Authentication Header

UDP 4500 IPSec NAT Traversal

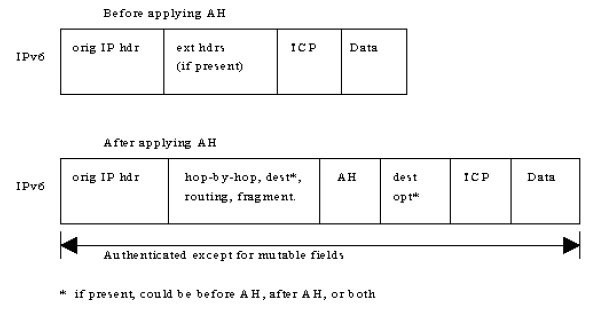

In IPv6, AH is an extension header that authenticates all headers and data after it’s location in the packet. The AH extension is added immediately after the original packet header, but before the transport header; also, the protocol field data in the original packet is replaced with 51, which denotes AH [1].

Figure 03: IPSec AH IPv6 Packet Format [4]

Without NAT traversal, NAT incompatibility is not a problem for gateway to gateway connections, such as those between routers for management purposes. With AH, routers communication about route updates can be sure that the information they receive is correct and is coming from who it should be. The lack of NAT support and lack of encryption make AH less popular than ESP in most applications and environments. Nonetheless, the more robust packet verification options make it useful in some environments where privacy is not a concern but payload correctness is.

Encapsulating Security Payloads

Similar to traditional VPNs, ESP can provide encrypted and authenticated point to point tunneling. IPSec was designed to be highly flexible and extensible, allowing clients to use any encryption algorithm that they both have access to. However, to ensure interoperability, there are definitions of some algorithms that must be supported by any implementation [1]. These are as follows from the original RFC on IPSec required algorithms for ESP [12]:

Requirement Encryption Algorithm (notes)

----------- --------------------------

MUST NULL [RFC2410] (1)

MUST AES-CBC with 128-bit keys [RFC3602]

MUST TripleDES-CBC [RFC2451]

SHOULD AES-CTR [RFC3686]

SHOULD NOT DES-CBC [RFC2405] (2)

The use of symmetric encryption algorithms allow higher performance and are easier to implement in hardware, which is especially important in speciality devices such as routers [2]. Of the required algorithms, none provide data integrity checks. Combined Mode algorithms provide both, and offer significant performance and efficiency improvements over an AH + ESP configuration. Combined Mode algorithms are now preferred for IEEE 802.11i (Wifi) networks for this reason [13]. The NULL algorithm denotes when ESP’s authentication or encryption capabilities are being ignored; when no encryption or no authentication is desired. However, both the encryption and authentication algorithms may not be NULL.

While the previous algorithms are required, the endpoints of the connection are allowed to decide to use whatever they both have available. A popular, non-standard choice is Blowfish. Once decided, both ends create a Security Association (SA) and Security Parameter Index (SPI) which stores the specifications for the connection. This allows them to maintain multiple, unique connections, each with different connection specifications.

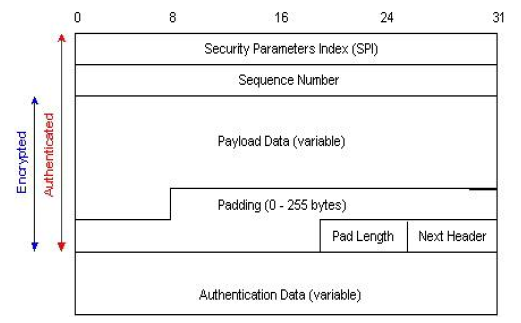

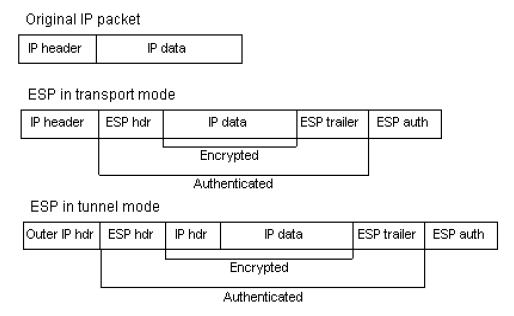

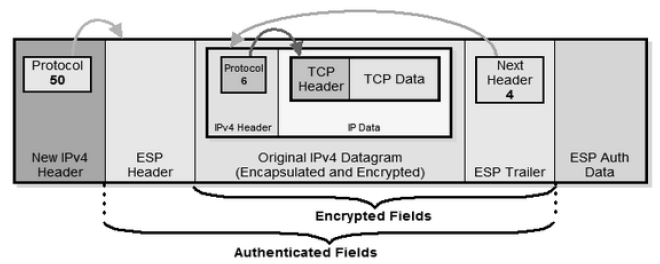

Unlike AH which simply precedes the packet, ESP surrounds the source packet. This is necessary to provide trailing padding for block-based encryption algorithms, as well to provide space for the ESP auth field. ESP authentication only covers ESP data, the source packet payload and its own header. Since the all the ESP fields are encrypted, it’s not possible to determine from the packet itself whether there is any authentication data at all. This is instead determined during the Security Association generation phase when the connection is made [9].

Figure 05: IPv6 ESP Header and Trailer [6]

AH and ESP are typically not used together since AH doesn't allow traffic to cross NAT and the authentication provided by ESP Combined algorithms is usually robust enough to ensure packet integrity. Nonetheless, they can be used together in which case AH precedes the ESP portion of packet. In IPv6, ESP is treated as an end-to-end payload, meaning it’s placed after the hop-by-hop, routing, and fragmentation extension headers.

Figure 06: ESP Tunnel and Transport Mode Packet Format

Security Associations and Parameters

During the connection establishing phase, the endpoints define which algorithms will be used, who each other are, and the connection type. This information is stored in a Security Association (SA) document. SAs are symmetric, meaning that on the other side, the addressed aren’t mirrored. An example SA and SP for 10.0.0.216 and 10.0.0.11, with manual keying, is given below [10]:

Here, the SA defines who the connection is between, which protocol to use, a Security Parameter Index (SPI), which cryptographic algorithm to use, and the shared secret key. These parameters are symmetric on both hosts.

add 10.0.0.11 10.0.0.216 esp 15701 -E 3des-cbc "123456789012123456789012";

add 10.0.0.216 10.0.0.11 esp 24501 -E 3des-cbc "123456789012123456789012";

The Security Policy defines the routing rules; what exactly is supposed to happen when a packet is sent from 10.0.0.216 to 10.0.0.11 or vice versa. The SP is not symmetric; this example if for the 10.0.0.216 host.

spdadd 10.0.0.216 10.0.0.11 any -P out ipsec

esp/transport//require

spdadd 10.0.0.11 10.0.0.216 any -P in ipsec

esp/transport//require

A Security Association is not a unique identifier for a connection, that’s the job of the Security Parameter. The SPI defines which SP to use, which is linked with an SA. Linux Advanced Routing & Traffic Control has an excellent quote for defining the difference, “... a Security Policy specifies WHAT we want; a Security Association describes HOW we want it.” [10]

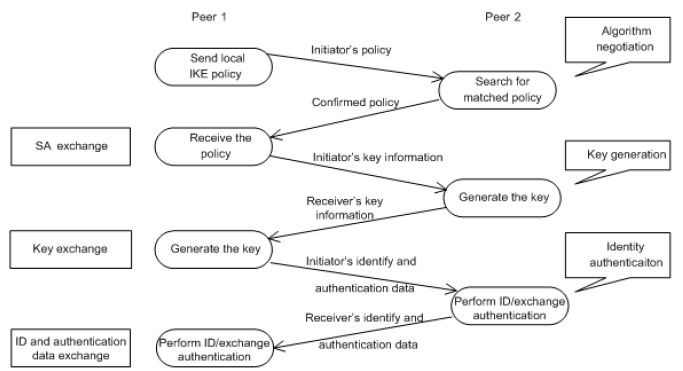

Internet Key Exchange

Manual key configuration is useful for some situations, but isn’t always practical. When dealing with gateways, it’s not too much work to securely set up shared secrets between the endpoints. However once the shared secret is on both hosts, it’s no longer secret because it’s symmetric. To circumvent this problem, and/or if the endpoints are mobile hosts, it’s easier to use Internet Key Exchange (IKE) protocol. An IKE daemon running on the endpoints can provide session keys for use in either tunnel or transport mode.

In terms of SAs and SPs, IKE provides the Security Association. In Linux, when the kernel finds the SP without an accompanying SA, it will contact the IKE daemon to generate one. [10] IKE will then contact it’s equivalent on the other end of the connection and negotiate the connection parameters.

It’s also possible to set up automatic keying with asymmetric encryption, such as that provided with SSL, thanks to the flexibility provided by the IPSec suite. It’s not important that the public key exchange is encrypted, but it should be authenticated to prevent man-in-the-middle attacks. This is possible by having your keys signed by a certificate authority (CA).

Figure 07: IKE Communication Flow [11]

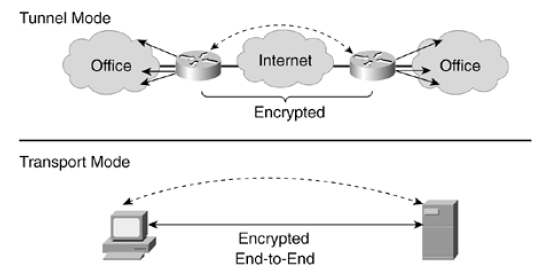

Operation Modes

IPSec provides two overarching modes, in which AH and ESP act slightly differently. Tunnel mode is most like a typical router to router VPN and is usually preconfigured. Transport mode is more like an Secure Shell (SSH) connection in that clients are typically hosts, not routers, and it’s not required that they know or trust each other before the connection begins.

Tunnel

As with a non-IPSec VPN, the entire client packet is encapsulated and encrypted within a new outer packet. The new outer packet contains the only the routing information needed to get the other point in the tunnel. Once it’s arrived at the gateway, typically a router, it will decrypt the packet based on the Security Associations that were defined during the tunnel creation. Next, it strips away the IPSec fields and pass the original packet along to its destination.

When configured between two routers, such as a branch office and headquarters of a business, tunnel mode provides full encryption and authentication without any client side configuration. All traffic meeting predefined specifications, such as a particular IP address range, will be caught by the router and sent through the tunnel. Configuration allows for some traffic to be untouched by IPSec and others to be handled by any number of IPSec tunnels.

Figure 08: IPv4 ESP Packet Format - IPSec Tunnel Mode [9]

Tunnel mode supports mixed IP versions between the inner and outer packets; eg. IPv6 over IPv4 and IPv4 over IPv6. The outer packet carries only the information required to get it to the next IPSec gateway, from which point it will be removed and the inner packet will be routed according to its specifications [5]. Similar to the nested routed in the Tor network, it is possible to encapsulate multiple IPSec packets within each other. Such a configuration would allow the same kind end-to-end anonymity that Tor provides, though there are no special provisions in IPSec to do this automatically.

IPSec tunneling by itself accomplishes it’s task of providing confidential and robust network connection, but doesn’t have support for multicast, dynamic Interior Gateway Protocol (IGP) routing, or non-IP protocols. However, this functionality can be gained by using IPSec in conjunction with other protocols, namely Generic Route Encapsulation (GRE) and Virtual Tunnel Interfaces [2]. These other protocols are not covered in this paper.

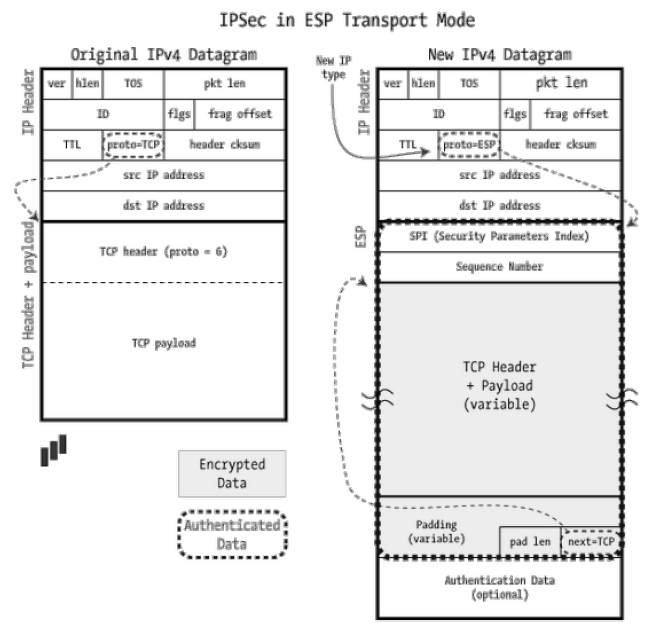

Transport

Transport mode is the default for IPSec, and is dissimilar to a VPN. Instead, it is a secured IP connection between two endpoints, such as a client and server. ESP and AH function differently in transport mode than in tunnel mode [14]. The differences in functionality between Tunnel and Transport mode are easily visualized by the graphic below.

Figure 09: Tunnel vs Transport Mode [15]

AH and ESP do not encapsulate the source packet like in Tunnel mode, and only encrypt or authenticate the payload portion. The ESP header goes before the source payload, with ESP trailer and auth immediately after the source payload. When used for authentication, ESP signs only the payload and it’s own information. AH follows the same pattern; the AH header is placed directly after the source packet header and before the payload [14]. You can have authentication and encryption in transport mode if you use AH and ESP in conjunction or a combined algorithm for ESP.

When a packet is sent, it’s header is modified to allow for the AH fields. When it’s received on the other end, the packet is reassembled to its original format before it’s handed off the to the process waiting for it. This is done at the IP level in the network stack, applications don’t have to know how to deal with IPSec modified packets.

Figure 10: IPSec ESP Transport Mode [9]

The demarcation between transport and tunnel mode isn’t specifically defined in a field. Instead, its inferred by the value of the next-header. If the next-header is IP, it means that this packet is encapsulating another packet.

Conclusion

IPSec is a suite of flexible and extensible protocols and standards designed by the IETF to provide built-in security to IP network traffic [1]. Its compatible with IPv4 and IPv6. It’s goal is to provide inherent security to IP, providing security and authentication to all IP traffic at the IP level in the network stack. IPSec provides provisions to ensure data integrity, authentication, replay avoidance, and confidentiality for all IP traffic. It is highly configurable, ubiquitous, and allows a wide range of options and modes, making it an excellent choice for network security.

References

-

Internetworking with TCP/IP

Comer, Douglas; 4th Edition, © 2000 Prentice Hall

-

RFC 4835, Cryptographic Algorithm Implementation Requirements for ESP and AH

-

IPv6 Essentials, Integrating IPv6 into your IPv4 Network

Hagen, Silvia; 3rd Edition, © Silvia Hagen, O’Reilly Media